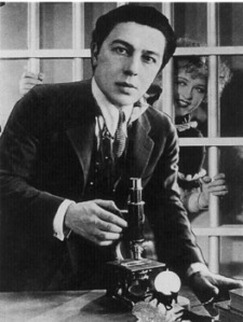

André Breton, photomontage by Max Ernst

by James Wedlake

'If in a cluster of grapes there are no two alike, why do you want me to describe this grape by the other, by all others, why do you want me to make a palatable grape? Our brains are dulled by the incurable mania of wanting to make the unknown classifiable.'

The above quotation is just a snippet of the inspiring thoughts of an ingenious man, Monsieur André Breton, taken from the 'First Surrealist Manifesto' of 1924, which I wholeheartedly implore you to read.

Though what exactly is it that Monsieur Breton is trying to say here? What does he want from us? Surely it is rather useful to have words, or to use the correct philosophical terminology, ' universals', that can be used to refer to a multiplicity of different things, or 'particulars'. It would indeed be rather confusing to have to refer to each and every grape by a specific name. I, in fact, find the word grape rather helpful in procuring the delicious fruit. So what is the problem with the word Monsieur Breton?

The point is, that when we use a word, like grape, to refer to some thing in the world, we become lazy in the way that we think about the world. As soon as we have identified the object in front of us as a grape our work is done. We know how to use it, that it is edible, what it will taste like, that it could be made into juice and so on and so forth. In short we have classified it and fit it into the pre-existing structure of language that determines what grapes can be used for and what they cannot.

Breton thinks that it is rather foolish to do so, and more than that, it is rather boring too. Breton's line of thought can be linked with Structuralism and Post-Structuralism. A Swiss linguist called Ferdinand de Saussure, a man with rather a lot of interesting ideas, claimed that the link between a word, what he called a 'signifier' and a concept, or 'signified', was not essential, but has only arisen through convention. Thus, the deeper point, is that meaning is subjective and moreover, it is arbitrary. A grape is not a grape in itself.

When we detect particular piece of sense data we are usually able to classify it. For instance, I might name a particular piece of visual sense data a purple colour. I may even go so far as to label it a grape. But as soon as I have done so, I have in fact limited its meaning.

Breton does not want us to limit meaning. Even more than that he does not want us to determine meaning according to rationality, logic or even worse, common sense. He wants us to interpret the world according to our subconscious, to fuse internal reality, or the dream, and external reality, the world, into a kind of 'surreality', so to speak.

This is why Breton loved anomalies. Anomalies prove that meaning is not a quality of the external world, but something we bring to it. The cliché example is, of course, the discovery by Europeans that there existed black swans in Australia when all swans were previously thought to be white. We have created words to refer to things, which we have found to have similar qualities, swans, for instance, but when there occurs an object that seems to have many of the qualities required to classify it using a particular word, such as swan, but has one quality that is so unusual, it is black, we are dumbstruck. It shows us that language cannot always represent the world.

There sometimes occur things that are not representable, that are incommunicable, that show that language is a subjective system of values that does not equate with the external world, as Jacques Derrida, another brilliantly thoughtful man and, apparently, a Post-Structuralist, has gone to lengths to demonstrate. If we impose language on the world, we miss out on the anomalies that show that rationality is not an objective, fixed approach to the world.

We should also be wary not just to look for differences on the scale of the black swan. As Breton points out, no two grapes are identical. Meaning is only possible when we pretend that there exist things that are the same, because in this way, we can make use of the world. If nothing had an identity, we could not identify it and we could not use it. But Breton does not care about using things, about being practical. In fact, the man hated work, instead opting to go on night time wanderings around the city of Paris.

Breton wanted us to see the world afresh, though our subconscious desires, through the eyes of Eros. He wanted us to seek out anomalies that show that some object we thought was something, could, in fact, be something else. And on that note, I will leave you to ponder a photograph aptly titled 'Untitled' by Man Ray of 1933. What could it be I wonder? Not a hat, I hope!

'If in a cluster of grapes there are no two alike, why do you want me to describe this grape by the other, by all others, why do you want me to make a palatable grape? Our brains are dulled by the incurable mania of wanting to make the unknown classifiable.'

The above quotation is just a snippet of the inspiring thoughts of an ingenious man, Monsieur André Breton, taken from the 'First Surrealist Manifesto' of 1924, which I wholeheartedly implore you to read.

Though what exactly is it that Monsieur Breton is trying to say here? What does he want from us? Surely it is rather useful to have words, or to use the correct philosophical terminology, ' universals', that can be used to refer to a multiplicity of different things, or 'particulars'. It would indeed be rather confusing to have to refer to each and every grape by a specific name. I, in fact, find the word grape rather helpful in procuring the delicious fruit. So what is the problem with the word Monsieur Breton?

The point is, that when we use a word, like grape, to refer to some thing in the world, we become lazy in the way that we think about the world. As soon as we have identified the object in front of us as a grape our work is done. We know how to use it, that it is edible, what it will taste like, that it could be made into juice and so on and so forth. In short we have classified it and fit it into the pre-existing structure of language that determines what grapes can be used for and what they cannot.

Breton thinks that it is rather foolish to do so, and more than that, it is rather boring too. Breton's line of thought can be linked with Structuralism and Post-Structuralism. A Swiss linguist called Ferdinand de Saussure, a man with rather a lot of interesting ideas, claimed that the link between a word, what he called a 'signifier' and a concept, or 'signified', was not essential, but has only arisen through convention. Thus, the deeper point, is that meaning is subjective and moreover, it is arbitrary. A grape is not a grape in itself.

When we detect particular piece of sense data we are usually able to classify it. For instance, I might name a particular piece of visual sense data a purple colour. I may even go so far as to label it a grape. But as soon as I have done so, I have in fact limited its meaning.

Breton does not want us to limit meaning. Even more than that he does not want us to determine meaning according to rationality, logic or even worse, common sense. He wants us to interpret the world according to our subconscious, to fuse internal reality, or the dream, and external reality, the world, into a kind of 'surreality', so to speak.

This is why Breton loved anomalies. Anomalies prove that meaning is not a quality of the external world, but something we bring to it. The cliché example is, of course, the discovery by Europeans that there existed black swans in Australia when all swans were previously thought to be white. We have created words to refer to things, which we have found to have similar qualities, swans, for instance, but when there occurs an object that seems to have many of the qualities required to classify it using a particular word, such as swan, but has one quality that is so unusual, it is black, we are dumbstruck. It shows us that language cannot always represent the world.

There sometimes occur things that are not representable, that are incommunicable, that show that language is a subjective system of values that does not equate with the external world, as Jacques Derrida, another brilliantly thoughtful man and, apparently, a Post-Structuralist, has gone to lengths to demonstrate. If we impose language on the world, we miss out on the anomalies that show that rationality is not an objective, fixed approach to the world.

We should also be wary not just to look for differences on the scale of the black swan. As Breton points out, no two grapes are identical. Meaning is only possible when we pretend that there exist things that are the same, because in this way, we can make use of the world. If nothing had an identity, we could not identify it and we could not use it. But Breton does not care about using things, about being practical. In fact, the man hated work, instead opting to go on night time wanderings around the city of Paris.

Breton wanted us to see the world afresh, though our subconscious desires, through the eyes of Eros. He wanted us to seek out anomalies that show that some object we thought was something, could, in fact, be something else. And on that note, I will leave you to ponder a photograph aptly titled 'Untitled' by Man Ray of 1933. What could it be I wonder? Not a hat, I hope!