|

The coach is at the door at last;

The eager children, mounting fast And kissing hands, in chorus sing: Good-bye, good-bye, to everything! To house and garden, field and lawn, The meadow-gates we swang upon, To pump and stable, tree and swing, Good-bye, good-bye, to everything! And fare you well for evermore, O ladder at the hayloft door, O hayloft where the cobwebs cling, Good-bye, good-bye, to everything! Crack goes the whip, and off we go; The trees and houses smaller grow; Last, round the woody turn we sing: Good-bye, good-bye, to everything! Robert Louis Stevenson Whilst lying sleepily and slightly feverish in bed in Nepal, I found this lovely lyrics video for Home by Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros and suddenly felt warmer, fuzzier and a little better for contracting tropical illnesses. So I thought maybe it could help anyone ailing with Freshers' flu. Pass it on :) Georgina Phillips

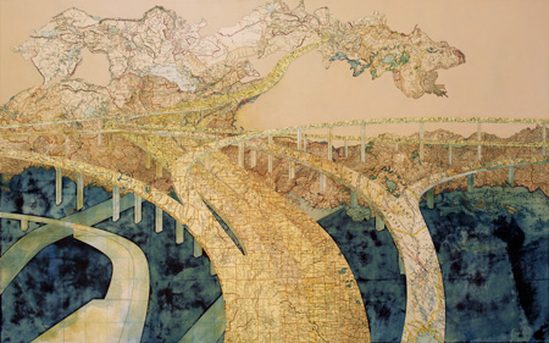

The word ‘collage’ has for a long time conjured up images of my younger self enthusiastically attacking old magazines, ripping faces out of the newspaper and uniting them indiscriminately under healthy blobs of glitter glue, feathers, fabric scraps and whatever else I could find. The anything-goes appeal of collage has always been undeniable, and has been beautifully explored by more grown-up artists as well as my littler cousins. In a culture where we’re trying desperately to recycle and re-use the things we accumulate, an art form which encourages you to do exactly that seems incredibly relevant. The use of found objects and recycled surfaces in art simultaneously plays to our concerns about a throwaway society and creates works layered with meaning; re-using images or scraps creates something fresh while still inviting the viewer to consider old uses and contexts. Images become part of other images; maps converge upon imaginary places; books say new things and headlines suddenly speak for different pictures, creating an intriguing dialogue between the ‘new’ work and its diverse components. Collage artists like Matthew Cusick use this richness to their advantage, selecting their materials to enhance the images they create. In Cusick’s visual world, a vast wave spills over with maps of different seas (Fiona’s Wave, 2005) to reveal an array of underwater cartography from different eras and parts of the world, while above another such ocean (Leviathan, 2008) inky constellation-splattered Biblical figures occupy the heavens. His collages range from these huge, mythical land and seascapes to the strange car-and-flower splices to be found in his Happy Endings series, created entirely of magazine clippings pasted onto panels and depicting what could be several horrific crashes- or, as suggested by titles such as Crown of Creation, some strange melding of nature and machinery. The mixture of the completely imaginary with the full-colour realism of materials such as maps and photographs is really beautifully explored by Cusick- and, indeed, by some of the artists in our very own Blake gallery (take a look!). You can also see more of Cusick’s work here: http://www.mattcusick.com.

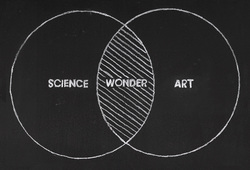

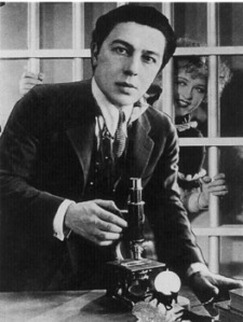

The Shins acting debut in Simple Song (apologies for advert at the beginning). Anyone else got any suggestions?  by John Medley-Hallam Freshers beware! You are about to be asked a question. One that is so powerfully divisive it splits not just you from your peers, but even college fellows from theirs; the question is thus: “So which are you then: arts or sciences?” And judgement passes, fostered by decades of prejudices, endowing the answerer with seemingly obvious social, behavioural and sartorial qualities. How are we to scale such a barrier to potential friendships? Just keep fighting the good fight; you always need people to argue with. But you won’t be arguing much longer. It is my great privilege to inform you that we have a solution at long last. Science is better than arts. At the very least, ‘Science is more beautiful than art’ according to esteemed Guardian columnist, Jonathon Jones. Jones purports that it is because of the lack of aesthetic prowess that “science seems to dwarf today's art”. Without insult, this man does not understand the point of science. I wish, at least, he could try to use some objective reasoning when claiming science to be the superior. Instead he revels in making the most ridiculous comparison between pictures of the Eagle Nebula and the new Damien Hirst exhibition. Just because the Hubble telescope can take prettier photos than my friend’s Holga doesn’t mean scientists find more beauty in their work. What is beauty anyway? What form does it take? I’m sure artists are far more familiar with such questions than scientists are. Don’t let me give you the impression that I don’t value this article. I value its peculiarity. By that I mean that it is rather odd that an art critic can move so swiftly from having mutual respect to downright sycophancy. I’ll give my favourite example where he concludes that “in the 21st century, art rarely rivals the capacity for wonder that modern science displays in such dazzling abundance”. Oh why thank you sir, you do flatter me so! Did I mention I study chemistry? Am I biased towards the arts? In short, no. My bias is simply towards finding the truth. Furthermore, I’d hope that in search for such a thing I would not be so stubborn or ignorant to think that the scientific method is the only one. Eastern philosophy nicely establishes three different approaches to understanding the nature of reality, chiefly expressed through the study of parts, causes and conditions, and thought. For me, there is a clear distinction between the first two approaches, essentially modern science, and the last, the realm of art. Here’s my point: you just cannot meaningfully compare them. They have different methods, and ask different questions. I am guessing you still wish to choose a side. So be it, after all your degree depends on it- but I implore you not to hold your prejudices forever. The current economic status clearly puts pressure on what we value as a society; the Arts Council England alone lost 29.6% of its government funding last year, averaging to 15% across the country. For once in this historically bloody battle, science seems to be on top. Not by means of its inherent beauty, but rather because it is easier to maintain the status quo with a populous spellbound by technology. Don’t accede to the science-machine. References: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jason-silva/at-ted-active-2011-scienc_b_832677.html http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2011/mar/30/arts-council-england-funding-cuts http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2012/sep/19/science-more-beautiful-than-art  André Breton, photomontage by Max Ernst by James Wedlake 'If in a cluster of grapes there are no two alike, why do you want me to describe this grape by the other, by all others, why do you want me to make a palatable grape? Our brains are dulled by the incurable mania of wanting to make the unknown classifiable.' The above quotation is just a snippet of the inspiring thoughts of an ingenious man, Monsieur André Breton, taken from the 'First Surrealist Manifesto' of 1924, which I wholeheartedly implore you to read. Though what exactly is it that Monsieur Breton is trying to say here? What does he want from us? Surely it is rather useful to have words, or to use the correct philosophical terminology, ' universals', that can be used to refer to a multiplicity of different things, or 'particulars'. It would indeed be rather confusing to have to refer to each and every grape by a specific name. I, in fact, find the word grape rather helpful in procuring the delicious fruit. So what is the problem with the word Monsieur Breton? The point is, that when we use a word, like grape, to refer to some thing in the world, we become lazy in the way that we think about the world. As soon as we have identified the object in front of us as a grape our work is done. We know how to use it, that it is edible, what it will taste like, that it could be made into juice and so on and so forth. In short we have classified it and fit it into the pre-existing structure of language that determines what grapes can be used for and what they cannot. Breton thinks that it is rather foolish to do so, and more than that, it is rather boring too. Breton's line of thought can be linked with Structuralism and Post-Structuralism. A Swiss linguist called Ferdinand de Saussure, a man with rather a lot of interesting ideas, claimed that the link between a word, what he called a 'signifier' and a concept, or 'signified', was not essential, but has only arisen through convention. Thus, the deeper point, is that meaning is subjective and moreover, it is arbitrary. A grape is not a grape in itself. When we detect particular piece of sense data we are usually able to classify it. For instance, I might name a particular piece of visual sense data a purple colour. I may even go so far as to label it a grape. But as soon as I have done so, I have in fact limited its meaning. Breton does not want us to limit meaning. Even more than that he does not want us to determine meaning according to rationality, logic or even worse, common sense. He wants us to interpret the world according to our subconscious, to fuse internal reality, or the dream, and external reality, the world, into a kind of 'surreality', so to speak. This is why Breton loved anomalies. Anomalies prove that meaning is not a quality of the external world, but something we bring to it. The cliché example is, of course, the discovery by Europeans that there existed black swans in Australia when all swans were previously thought to be white. We have created words to refer to things, which we have found to have similar qualities, swans, for instance, but when there occurs an object that seems to have many of the qualities required to classify it using a particular word, such as swan, but has one quality that is so unusual, it is black, we are dumbstruck. It shows us that language cannot always represent the world. There sometimes occur things that are not representable, that are incommunicable, that show that language is a subjective system of values that does not equate with the external world, as Jacques Derrida, another brilliantly thoughtful man and, apparently, a Post-Structuralist, has gone to lengths to demonstrate. If we impose language on the world, we miss out on the anomalies that show that rationality is not an objective, fixed approach to the world. We should also be wary not just to look for differences on the scale of the black swan. As Breton points out, no two grapes are identical. Meaning is only possible when we pretend that there exist things that are the same, because in this way, we can make use of the world. If nothing had an identity, we could not identify it and we could not use it. But Breton does not care about using things, about being practical. In fact, the man hated work, instead opting to go on night time wanderings around the city of Paris. Breton wanted us to see the world afresh, though our subconscious desires, through the eyes of Eros. He wanted us to seek out anomalies that show that some object we thought was something, could, in fact, be something else. And on that note, I will leave you to ponder a photograph aptly titled 'Untitled' by Man Ray of 1933. What could it be I wonder? Not a hat, I hope! After ‘how many years have you got left now at uni?’ and the following remarks about time flying, the next question is almost always: ‘so what are you going to do next?’ Though it might only be asked out of vague curiosity, were you to reply with your plans to live in a shed, join a cult or just do nothing at all for a while, you could expect a surprised and alarmed response. As the bright young things that made it through university, there’s undeniably a certain expectation for what our next steps are going to be.

With adverts for graduate schemes piling high in my inbox, I can’t help but feel the pressure to start carving my career, to walk the well-trodden path of many university students that begins with my move to the big city, and ends up at successful settled suburban life when I hit my thirties. And although I know there’s little chance that I’ll buck the trend and leave Cambridge to live in a commune for the rest of my days, there’s a large part of me that wants to rebel against this expectation about what shape my life will take. The illusion of there being an ‘order’ that ought to be followed. We’re so used to the idea that one’s in their prime during their twenties and thirties that we’re burdened with the belief that we may become a successful and enterprising individual now, or not at all. So many of history’s greats are celebrated because of their success in their early years: Mendelssohn composed his spectacular octet at 16, Orson Welles directed Citizen Kane at 25 and Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d'Avignon aged 26. As a result, we mistakenly jump to the conclusion that geniuses and prodigies are one and the same. But as Sigríður Níelsdóttir, an Icelandic gran and the star of the arthouse film Grandma Lo-fi proves, this is most definitely not the case. At the tender age of seventy, Sigríður Níelsdóttir started recording and releasing her own music straight from her living room. Seven years later she had 59 albums to her name and more than 600 songs; an eccentric myriad of compositions mixing her pets purrs and coos, found toys, kitchen percussion and Cassio keyboards. Before long she became a cult figure in the Icelandic music scene. Grandma Lo-fi follows this funky lady over 8 years, capturing the most creative period of her life. A late bloomer, we might say, but only ‘late’ by our standards of what the right time for success is. Look around, and there are many whose main achievements come years later than is commonly expected: Julia Child didn’t start teaching cookery until nearly 40; Clint Eastwood directed his first film at 41 and Joseph Conrad barely spoke a word of English until he was 21 – he published his first work aged 37. It’s understandable why this myth has developed – in a world which worships the supermum who has a fantastic career and can juggle three children, achieving ‘everything’ is certainly made easier when you reach for success in your early years. But as Sigríður Níelsdóttir shows, out twenties are not necessarily our only defining years, nor are we on a steady decline forever after. Our achievements come in all shapes and forms, and like Grandma Lo-fi, it would do us no harm to shake up the order in which we attain them. Grandma Lo-Fi: the Basement Tapes of Sigríður Níelsdóttir will be shown tonight at 8pm on the roof of The Varsity Hotel in Cambridge as part of the Cambridge Film Festival. £10 concession tickets for students and picturehouse members. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q6Jc5sYom30 Last week, I took a half-full disposable camera to a family party and shot a few badly composed photographs of my cousins doing leggy handstands on a bed. The shutter had barely released before they were clamouring for a look at their own pixelated faces. My sister and I giggled a bit as we tried to explain the ancient concept of film, quickly realising that no little cousin is ever going to get it. Somewhere between now and those faded photographs of you and your cousins taking on the world as Team Rocket in 1998, we’ve seen a massive, defiant and life-changing digital revolution. Today, thousands of images are

instantly available at just so many pushes of a button, and the low complexity and cost of going digital have catalysed a transition in popular photography from the qualitative to the very, very quantitative. At the same time, pictures have become more and more central to modern popular culture: the image finds us everywhere. In particular, the rise of social networking has given the image a certain dynamism, with Tumblr acting as an infinitely scrolling photographic shrine to fuckyeah! winners of the genetic lottery, whilst Facebook allows us to recreate our entire existence as one extensively captioned photograph. This is in combination with a speed of upload which reduces the distance between existence and documentation until the two are perfectly contemporaneous. We begin to posit part of our existence in images added immediately to the online profile of our lives, tightly braiding real life with its instant, imaginary representation. Not only do we begin to assume that memory is a predominantly image based function, but we start to lack the patience that memory requires. We become more sentimental towards the present than we the past, so homesick for unfinished moments that we feel compelled to immortalise them with all the alacrity that superfast broadband allows. We find ourselves in a position which allows us to quickly and efficiently represent our lives in images. But the more images we produce the more disposable they become, and more often than not they end their short lives in a Facebook landfill of removed tags and dodgy auto-enhance after one brief lark as someone’s cover photo. Digital photographs can all too easily become throwaway additions to a world already saturated with images; immediate, yes, but somehow unauthentic in comparison with the lives they imitate. Because digital photographs do not succeed negatives but exist immediately, they do not develop or become, they just are. Unlike analogue photography, which requires multiple processes for a perishable, physical outcome, digital photography instantaneously arranges a series of immortal pixels which exist now as they always will. For a generation whose idea of memory is conditioned by sepia hued prints of stylish grandparents and rolls of 35mm developed on the hour at Boots, it can be tricky to reconcile the need for immediate representation with an unauthentic feel or aesthetic. Digital photographs are ageless and timeless, with an unfitting, unfulfilling lack of physicality. They don’t seem like vehicles of memory simply because they will not age as we age. Corporate communities like Lomography have latched on to this attitude by marketing a photographic culture which is careless and authentic, shot ‘from the hip’ rather than deliberated as a potential profile picture. Still, actual analogue photography doesn’t go quite far enough. If we had the patience, digital photographs themselves would eventually look dated, but we barely have the patience to shoot a roll of 36 and twiddle our thumbs whilst it’s being processed. It is here that Fauxmo usurps Lomo. Software like Instagram imitates the effects of analogue photography, lending a feel of physicality, permanence and gravity to our photographs and somehow, as a result, to our life as it passes and is documented. It provides a satisfying and ‘authentic’ means of representing our future-to-be, that is, the past we already anticipate looking back on. Because of their digital format, the results have an immediacy which beats contemporaneity: we publish photographs of food we haven’t yet eaten, drinks we haven’t yet drunk and outfits we haven’t yet worn. At the same time, though, it allows us to translate our own, real experiences into something seemingly more real and more physical than pixels on a screen. Today, we want better than the best of both worlds, and Instagram gives us photography which is more instant than instant and more real than real.  by Shannon Keegan As we all begin to get our heads around the fact that summer is coming to an end and we’re heading back to the Bubble, I’m using my first Blake blog post to promote something happening in the area I call home. Art is certainly not the first thing that springs to mind when you think of Walthamstow. It’s part of Waltham Forest; a borough of London sandwiched between Hackney and Essex, and is generally portrayed in a fairly negative, and certainly non-creative, light. Unless you consider the setting fire to some bins during the 2011 Summer Riots creative, that is. (Come on guys, Tottenham completely upstaged us.) However, Walthamstow has its charms, most relevant to this blog is its annual E17 Art Trail. 2012 will be its 8th year, and the longest, best advertised and talked about one yet. From the 1st to the 16th of September, over a thousand local artists display their art around the area. The art forms and exhibition spaces are equally diverse, turning Walthamstow’s lack of official gallery space into an advantage by letting people to really use their imagination. It is the unpredictability of the trail that I love, the informal feeling of art spread across your hometown, ready to be stumbled across in the most unlikely places with a childish, treasure hunt like satisfaction, (my current favourite is the life size plaster cast woman sitting at Walthamstow Central bus station). This year has sparked a really positive reaction, with social networking sites like Facebook enabling people to share their art they have ‘found’, and their opinions on it. The submission process is open, allowing professional artists to be joined by local residents in the challenge of decorating and performing in their hometown, promoting the appreciation of art, and indeed tackling the misconception of art being something ‘normal’ people can’t join in with and experience. Not that it’s likely that anyone will make the last couple of days of the Art Trail, but I think the concept is applicable to the Blake Society in that it opens up art to everyone, and promotes the idea that the term ‘Art’ can be taken to mean a great deal more than the stuffy, elitist world many imagine it to be. Bring on the Blove. The main website: http://www.e17arttrail.co.uk/ A supporting Walthamstow arts development organisation: http://www.artillery.org.uk/ Some of last year’s exhibitions: http://www.mburtonphoto.com/2012/01/e17-art-trail-in-90-seconds/ |

Author.The Blake Society is THE Downing College society for all arts and humanities students and anyone interested in arts-type things. Archives

February 2016

|